France-Soir

Information warfare: human control, censorship and trust tested by the health crisis analyzed at NATO

Abstract: In information warfare, where AI and social media amplify narratives and censorship, public trust is faltering. The NATO HFM-377 symposium (2024) proposes frameworks like AMLAS, LoR, and AIMS to ensure ethical human control over military AI, in the face of computational propaganda. But Boeke and Mittemeijer-Ooteman's study on COVID-19 exposes massive censorship: truths about the virus's origin, aerosols, masks, vaccines, and early treatments have been suppressed as disinformation by governments, the WHO, opaque fact-checkers, and AI algorithms. This repression, orchestrated under political pressure and marred by conflicts of interest, recalls historical excesses: Galileo censored for heliocentrism, Hertel muzzled for his work on microwaves, the Recovery study manipulating hydroxychloroquine at toxic doses, and Wakefield demonized for his questions about the MMR vaccine. The marginalization of FranceSoir, wrongly accused of disinformation for its critical analyses, embodies this scandal.The impacts are devastating: science hampered, societies polarized, freedoms trampled. Restoring trust requires transparency, open debate, and ethical regulation: independent committees, audited fact-checkers, appeal mechanisms, and digital education. Without these, democracy risks succumbing to imposed truth, far removed from freedom and science.

Article

In a world where a tweet can ignite a global controversy and artificial intelligence (AI) can censor a truth with a click, information warfare is redefining the stakes of power, truth, and democracy. Recent documents (458 pages of analysis and 383 pages of PowerPoint presentations) from the NATO HFM-377 symposium organized by the NATO Science and Technology Council (October 2024, Amsterdam), and more specifically from Boeke and Mittemeijer-Ooteman's analysis of censorship during the COVID-19 crisis, shed a harsh light on these challenges.

The objective of the HFM (Human Factors and Medicine) symposium was to explore how to ensure Meaningful Human Control (MHC) over AI systems in military operations, while the specific analysis on the covid crisis, document MP-HFM-377-21 reveals massive censorship of scientific hypotheses, wrongly labeled as disinformation, during the pandemic. These practices, reminiscent of precedents such as the persecutions of Galileo, the Hertel jurisprudence, or the fraudulent Recovery study, have shattered public trust and polarized societies.

For the public, these issues touch on freedom of expression, transparency, and resilience against manipulation. This article deciphers the symposium's technical frameworks (AMLAS, LoR, AIMS), definitions of disinformation, censorship actors, and societal impacts. Media outlets like France-Soir have been marginalized for daring to question official narratives, highlighting the urgent need to protect fundamental rights, democratic debate, and restore trust.

When information becomes a weapon

With an invisible battlefield, where the weapons are algorithms, hashtags, and narratives, welcome to the information war. A terrain where a propaganda campaign can manipulate millions of people in a matter of hours. The NATO HFM-377 symposium, held in Amsterdam in October 2024, brought together 180 experts from 28 countries to answer a burning question: "how to keep humans in control in the face of ever more powerful AI systems?" And Boeke and Mittemeijer-Ooteman's analysis revisits the COVID-19 crisis, revealing how governments, international organizations, and algorithms have suppressed scientific truths under the guise of combating misinformation.

What is disinformation? According to the symposium and the documents France-Soir was able to consult, misinformation refers to false information disseminated without the intention to deceive, while disinformation implies a malicious intention, aimed at harm or profit (European Union, 2018). These definitions, clear on paper, have collided with a chaotic reality during the pandemic, where legitimate hypotheses have been swept aside as "conspiracies" or "conspiracy theories". This double prism – technical and historical – invites reflection:

How to manage information without sacrificing freedom or truth?

NATO Symposium : Keeping Humans at the Heart of AI (Artificial Intelligence)

Tools to tame AI : At the heart of the symposium, a group of researchers led by Lange proposes two frameworks for certifying AI-based autonomous systems, ensuring they remain aligned with human intentions.

The first, AMLAS (Assurance of Machine Learning for Autonomous Systems), is a six-step methodology that integrates security into the design of machine learning models. Imagine an AI system tasked with detecting a computational propaganda campaign on social media: AMLAS ensures that it doesn't mistakenly spread biased information or target vulnerable groups.

The second, LoR (Level of Rigor), assesses the rigor of the development of these systems, with confidence levels adapted to the risks. In a sensitive military mission, a high LoR requires exhaustive testing to avoid slippage.

These tools aren't just for military strategists. They address a shared fear : that AI will become a black box, making uncontrolled decisions. "It's like installing an emergency brake on a self-driving car," explains one engineer at the symposium.

But convincing the public will require more than promises – it will require transparency.

AIMS: AI, a teammate under surveillance

Another analysis, by Cooke et al., presents the AI Manager System (AIMS), a system that monitors human-machine teams in real time in complex operations, such as space missions or multi-domain operations (land, air, cyber). AIMS uses sensors to analyze communications, operator physiology, and positioning. When a failure or cognitive overload is detected, AIMS proposes solutions to stabilize the system. A proof of concept shows that it can distinguish a resilient response (which restores balance) from a fragile response.

For the public, AIMS evokes a future where AI acts as a reliable teammate, but always under human supervision. "It's a tool that can save lives, but only if operators know how to use it," notes one researcher. This reliance on the human factor is a universal lesson, also valid for citizens confronted with automated technologies, from voice assistants to recommendation algorithms.

Humans at every stage

Boardman and McNeish, from the UK Ministry of Defence's (MOD) Science and Technology Department, drawing on four years of research by NATO's HFM330 group, emphasize the importance of appropriate human oversight at each phase of the AI systems lifecycle: design, development, and deployment. This approach allocates tasks between humans and machines to optimize performance while respecting ethical standards. For example, in combating a propaganda campaign, AI can analyze millions of tweets, but a human must validate the conclusions to avoid bias.

This principle is reassuring: AI is not a master, but a tool. For the public, it is a promise that the technology can be domesticated, provided that the processes are transparent and the operators are trained.

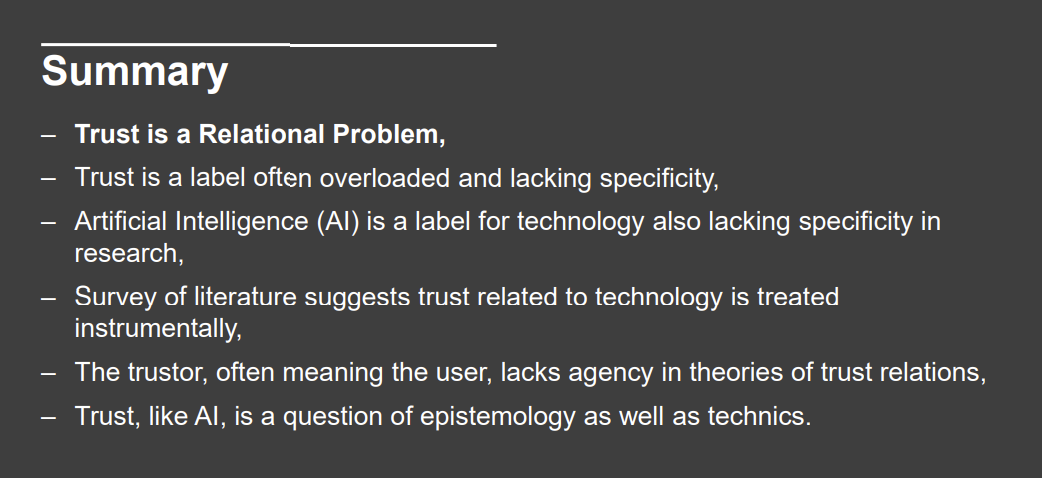

Trust, a socio-technical puzzle

Dr. Barrett-Taylor, a defense and security expert, and Dr. Byrne offer a novel vision: AI is not an isolated entity, but a network of actors —humans, institutions, and technologies. Their approach, based on the theory of socio-technical assemblages, distinguishes trust (in the institutions that create AI) from dependence (on the technology itself). "Trusting an AI means first trusting those who designed it" explains Byrne. This means that transparency from developers and regulators is crucial.

For the general public, this framework demystifies AI, often perceived as a magic box. It reminds us that trust is based on human relationships—a key message in an era of growing distrust of institutions.

Combating propaganda with ethics

Philosopher Santoni de Sio, Professor of Ethics and Technology at Eindhoven University, proposes combining Value-Sensitive Design (VSD), which integrates values like justice and freedom by design, with MHC. This ensures that AI systems remain responsive to human intentions and responsible. But challenges remain: AI can misinterpret intentions, amplify biases, or conflict with competing values, such as security versus freedom of expression.

For the public, VSD is a beacon of hope: AI systems aligned with democratic values.

But we must ensure that these values are defined with citizen participation, not just by elites in control.

Censorship during Covid-19, a sacrificed truth

Large-scale censorship

Between 2020 and 2023, the fight against misinformation reached unprecedented proportions. According to Boeke and Mittemeijer-Ooteman's analysis, Facebook removed 20 million COVID-19-related posts, and YouTube removed 1 million videos, often based on reports from anonymous fact-checkers or World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines. Governments, such as the White House, exerted political pressure to censor content, while AI algorithms amplified these removals without contextual analysis.

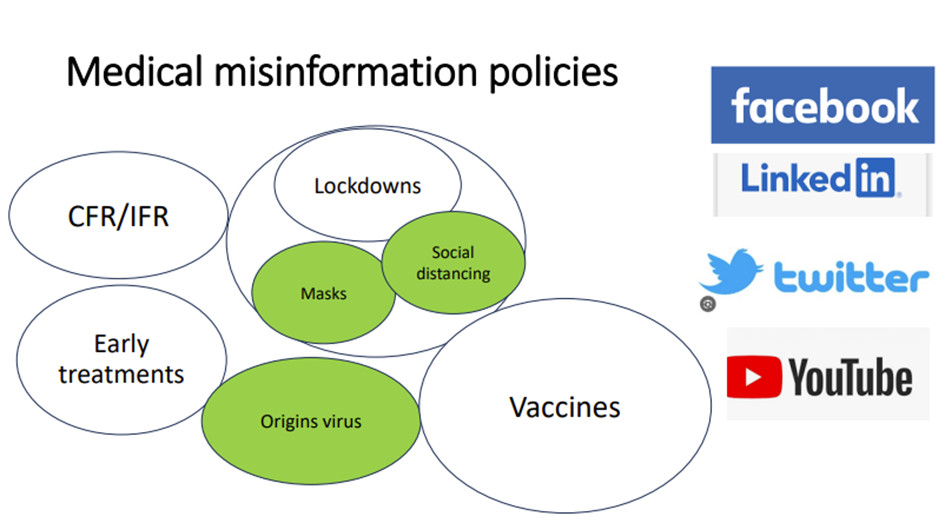

Three cases illustrate this drift:

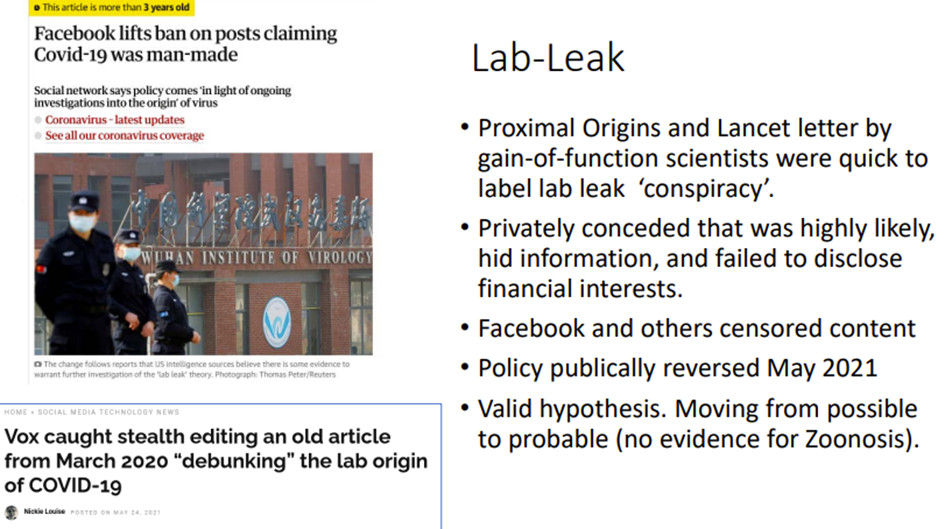

- The virus lab leak hypothesis : Described as a "racist conspiracy" this hypothesis was censored on social media until the WHO and the United States recognized it as plausible in 2021, well after Professor Montagnier described the molecular clockwork of the virus inserts. Conflicts of interest, such as the links between the Lancet Letter authors and the Wuhan Institute of Virology, have revealed a manipulation of the scientific debate.

- Aerosol transmission : The WHO has downplayed this mode of transmission, prioritizing droplets and contaminated surfaces. Scientists advocating for ventilation, such as Maurice de Hond, have been banned from platforms like LinkedIn.

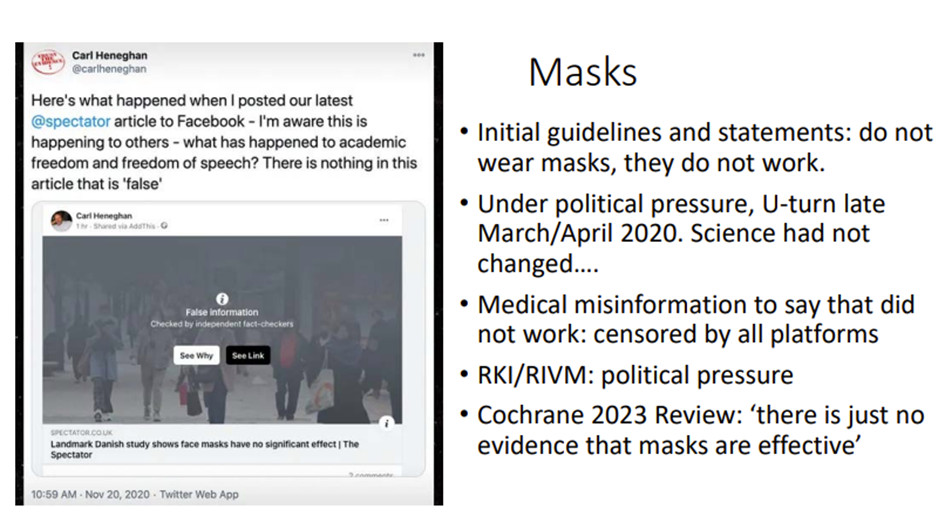

- Mask effectiveness : Despite the lack of solid evidence, masks have become mandatory. Studies, such as that of Heneghan and Jefferson, showing a limited effect, have been removed by Facebook, which added " misinformation" warnings.

Vaccines and early treatments have also been heavily censored, though Boeke's analysis does not go into detail. Virologists and vaccinologists have been "suspended" for questioning the efficacy or risks of vaccines, or for exploring early treatments. Others, like Jay Bhattacharya, were declared "fringe scientists" for questioning the effectiveness of lockdown measures.

This censorship has stifled crucial debates, leaving the public in the dark.

Who decides what is "disinformation"?

The assessment of disinformation was controlled by a complex network:

First, governments pushed platforms to act, sometimes under threat of regulation. Then, the World Health Organization (WHO) made statements, often hasty, that served as a reference for fact-checkers, without the media, or news agencies like AFP, verifying these statements. An argument of authority that is found used by fact-checkers - pseudo-journalists or anonymous people with biased reasoning who contributed to whitewashing information by flagging content without transparency. Finally, AI algorithms that once content was marked as disinformation, automatically deleted similar publications, amplifying errors, without any human intervention. True content or weak signals were marked as disinformation leading to type 1 errors (a true hypothesis that is mistakenly rejected) and type 2 errors (the hypothesis is mistakenly accepted).

This opacity recalls historical precedents where authorities imposed their truth, to the detriment of science and freedom.

Impacts, broken trust

Censorship had far-reaching consequences.

First of all, in science, because by muzzling the debate, censorship has delayed advances, such as the recognition of transmission by aerosols.

Then, on society : in 2021, 57% of those surveyed by the Edelman Trust Barometer believed that leaders were exaggerating the dangers of the virus. Censorship has polarized societies, with pro-maskers fearing the unmasked.

Finally, on human rights. The suppression of valid information violated freedom of expression and the right to information, particularly for experimental measures such as masks.

The excesses of censorship and the lessons of the past

Misuse of moderation tools

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted a disturbing truth: tools designed to protect against misinformation can become instruments of censorship when misused. AI algorithms, guided by opaque fact-checkers and biased institutions, have suppressed scientific truths under the guise of misinformation, causing lasting damage to public trust.

Several examples, both historical and contemporary, illustrate this drift.

- The first example dates back to the 17th century, with Galileo. Condemned by the Inquisition for defending heliocentrism, Galileo was censored by a religious authority imposing its truth. His hypothesis, deemed heretical, was nevertheless correct, but it took decades for it to be recognized. Similarly, during COVID-19, scientists like Alina Chan, who supported the lab leak hypothesis, were marginalized, labeled conspiracy theorists, even though their hypothesis is now considered plausible.

- The second example concerns the Hertel case lawof the 1990s. Hans Hertel, a Swiss scientist, was prosecuted for publishing a study suggesting that microwaves spoiled food. Despite evidence, he was censored by industry interests and authorities, who accused him of spreading disinformation. The European Court of Human Rights ultimately recognized a violation of his freedom of expression, highlighting the danger of letting established powers define the truth. This case resonates with the censorship of scientists during COVID-19, such as those advocating for ventilation against aerosol transmission.

- A more recent example is the Recovery study, a British study conducted in 2020, one of whose arms tested hydroxychloroquine. Designed to test this drug against covid-19, the study administered toxic doses (2400 mg on the first day 9600 mg over 10 days, well beyond the recommendations and doses considered toxic) to hospitalized patients, therefore at an advanced stage of the disease. The results, showing a lack of efficacy and a significant mortality (27%) but not statistically different from the control arm, were used to discredit hydroxychloroquine worldwide, leading to its abandonment as a potential treatment.

- However, critics have denounced fraudulent manipulation : the excessive doses appear either to be an error on the part of the investigators or intended to ensure the failure of the drug, possibly under the influence of pharmaceutical interests favoring more expensive treatments, such as remdesivir; or even the vaccine, because the absence of a drug alternative, the fourth condition for the approval of a vaccine, left them free to do so. Despite these warnings, voices denouncing the study were censored, labeled as disinformation, and platforms like Twitter and YouTube deleted publications on this scandal denounced by France-Soir. This censorship delayed a legitimate debate on early treatments, potentially depriving patients of viable options.

- Another notable case is the controversy surrounding Andrew Wakefield's 1998 study, which suggested a link between the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine and autism. Although the study was criticized for methodological flaws, Wakefield was delisted and his work labeled misinformation by health authorities and the media. Platforms systematically censored discussions of this study, even nuanced ones, under the guise of protecting public health. Yet, years later, independent studies explored possible links between vaccines and rare side effects, showing that Wakefield's questions, while clumsy, deserved scientific debate. Robert Kennedy Jr. and Jay Bhattacharya demanded data from vaccine manufacturers and recently mandated placebo testing for vaccines. This premature censorship fueled vaccine distrust, a boomerang effect that authorities had not anticipated.

In all these cases, moderation tools—fact-checkers and algorithms—were misused to impose an official truth, stifling valid hypotheses. The marginalization of critical media outlets like France-Soir, which exposed the Recovery study scandal and other inconsistencies, illustrates this phenomenon. Far from spreading disinformation, France-Soir acted as a weak signal, offering critical analysis of dominant narratives. By delisting it, Google and social media deprived the public of a voice essential to democratic debate, reinforcing polarization and mistrust.

Why does this happen?

The excesses of censorship during the COVID-19 crisis are not an accident, but the result of a convergence of systemic factors that have transformed moderation tools into instruments of oppression. The urgency of the health crisis has pushed governments to prioritize short-term compliance, to the detriment of scientific debate. Faced with global panic, leaders have sought to control the narrative to avoid chaos, exerting political pressure on platforms like Facebook and YouTube to remove any content deemed dangerous, even if it was based on legitimate assumptions.

This approach led to a blurred definition of disinformation, where scientific truths, such as hydroxychloroquine or aerosol transmission, were swept aside by often anonymous fact-checkers lacking scientific legitimacy. Conflicts of interest played a central role in these abuses, with institutions like the WHO, influenced by financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry or geopolitical pressures, imposing official narratives that served specific agendas.

For example, the Recovery study, funded in part by stakeholders (Welcome Trust, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) with vested interests in competing treatments, helped discredit hydroxychloroquine. Similarly, the authors of the Lancet Letter, linked to the Wuhan Institute of Virology, manipulated the debate on the origin of the virus, characterizing the lab leak hypothesis as a conspiracy to protect their own interests. The opacity of moderation processes exacerbated the problem, with unidentified fact-checkers lacking transparency about their methods and affiliations, while AI algorithms, programmed to spot keywords or patterns, removed content without contextual analysis.

This automation has amplified errors, such as the censorship of the otherwise rigorous Danish mask study. Together, these factors—urgency, conflicts of interest, and opacity—created an environment where truth was sacrificed for control, turning moderation tools into weapons against free speech and scientific progress.

Restoring trust: a challenge for the future

Restoring trust after institutional lies and massive censorship during the COVID-19 crisis is a herculean task, but essential to preserving democracy and the resilience of societies. Governments and institutions have broken a fundamental pact with the public by downplaying scientific truths, such as aerosol transmission, or exaggerating the effectiveness of masks without solid evidence. Censorship of credible voices, whether scientists denouncing the Recovery study or critical media outlets like France-Soir, has created a deep divide, fueling distrust and polarization. Citizens, feeling betrayed, are turning to alternative sources, often more reliable than the multi-million-dollar, government-funded mainstream media, while scientists, fearing for their careers, self-censor, limiting scientific progress.

This loss of legitimacy leaves institutions vulnerable, unable to mobilize the public in the face of future crises.

The analyzed documents from the NATO HFM-377 symposium offer insights into how to address this challenge. The NATO symposium emphasizes transparency as the foundation of trust, emphasizing that institutions must be accountable for their decisions. Publishing moderation criteria, conflicts of interest, and decision-making processes is a first step toward regaining public trust. Similarly, frameworks like AMLAS and LoR demonstrate the importance of rigorous human oversight to prevent algorithmic abuse. Applied to censorship, this means creating independent committees, composed of scientists, lawyers, and citizens, to evaluate disinformation with transparency and fairness. The Value-Sensitive Design (VSD) approach, which integrates values like justice and freedom into the design of AI systems, can also guide the creation of moderation tools that respect human rights.

The COVID-19 analysis, meanwhile, concludes that censorship is counterproductive, exacerbating distrust rather than dispelling it. It advocates for open debate, where scientific hypotheses, even controversial ones, are discussed rather than suppressed. This means acknowledging past mistakes, such as the censorship of the lab leak hypothesis or critiques of the Recovery study, and reintegrating marginalized voices into the public debate. For example, the scientists who denounced the toxic doses of hydroxychloroquine in Recovery deserve a platform to share their analyses, as do the critical media outlets that have served as gatekeepers.

Moving forward, several concrete actions are needed. First, fact-checkers must be subject to total transparency, publishing their methods, affiliations, and sources to avoid bias. Second, platforms must establish appeal mechanisms for content removed by algorithms, ensuring human oversight and procedural justice. Finally, digital education must become a priority, training the public to evaluate sources and recognize manipulation without resorting to censorship.

These measures, inspired by the lessons of the crisis and the framework of the symposium, aim to rebuild a social contract based on honesty, transparency, and respect for fundamental freedoms. As a Dutch proverb quoted in the study says:

" Trust comes on foot and leaves on horseback." It's time to take the first steps.

Conclusion

The NATO HFM-377 symposium and its analysis of censorship during COVID-19 reveal the tensions at the heart of the information war. Frameworks like AMLAS, LoR, and AIMS offer solutions for responsible AI, while the crisis exposes the dangers of censorship, which has suppressed truths about the origin of the virus, aerosols, masks, vaccines, and early treatments. The excesses of moderation tools, illustrated by the cases of Galileo, Hertel, the Recovery study, and all the scientific controversies, show how authorities can impose an official truth at the expense of science. The marginalization of critical media like France-Soir, far from being disinformation, was a weak signal of critical analysis essential to democratic debate.

Restoring trust requires transparency, open debate, and ethical regulation. By drawing on the lessons of the past and the frameworks of the present, we can build a future where AI serves humanity without compromising freedom or truth. The road will be long, but democracy depends on it.